Octavia, 键盘手和古风爵士,逃离舒适圈,有只英短叫八爷

02新手必读

现在翻译组成员由牛津,耶鲁,LSE,纽卡斯尔,曼大,爱大,圣三一,NUS,墨大,北大,北外,北二外,北语,外交,交大,人大,上外,浙大等70多名因为情怀兴趣爱好集合到一起的译者组成,组内现在有catti一笔20+,博士8人,如果大家有兴趣且符合条件请加入我们,可以参看帖子

五大翻译组成员介绍:

1.关于阅读经济学人()

()

2.为什么希望大家能点下右下角“在看”或者留言?

在看越多,留言越多,证明大家对翻译组的认可,因为我们不收大家任何费用,但是简单的点击一下在看,却能给翻译组成员带来无尽的动力,有了动力才能更好的为大家提供更好的翻译作品,也就能够找到更好的人,这是一个正向的循环。

精读|翻译|词组

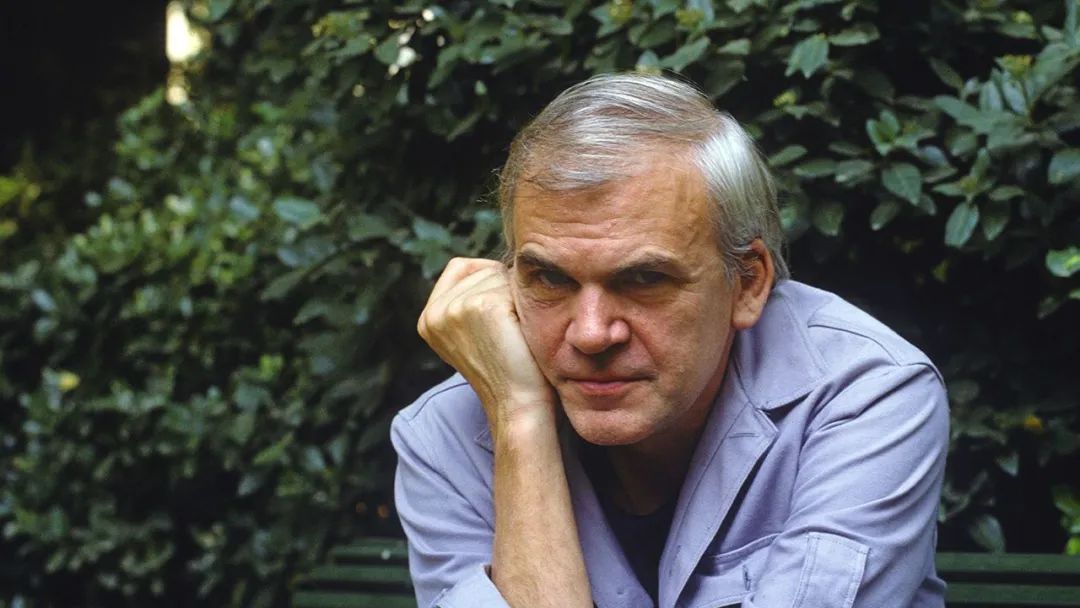

Milan Kundera

米兰•昆德拉

英文部分选自经济学人20230722期讣告板块

Milan Kundera

米兰•昆德拉

When angels laugh

当天使在欢笑

Milan Kundera, novelist and author of “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, died on July 11th, aged 94

《生命中不能承受之轻》作者,小说家米兰•昆德拉于7月11日逝世,享年94岁。

Just before the Prague Spring in 1968, when the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia seemed briefly to relax, Milan Kundera managed to publish a novel about a joke. The joke, sent by a young man to a girlfriend on a postcard, read: “Optimism is the opium of the people! A ‘healthy’ atmosphere stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky!” It landed the young man in a lot of trouble.

就在1968年“布拉格之春”的前夕,捷共政权似乎短暂地放松了一下,这也让米兰•昆德拉得以出版了一部围绕一个玩笑展开的小说——《玩笑》。这个玩笑是一个年轻男子写在给女朋友的明信片上的:“乐观主义是人民的鸦片!健康精神是冒傻气。托洛茨基万岁!”(书中)这名小伙子因为这个玩笑惹了大麻烦。

注释:

“乐观主义是人民的鸦片!健康精神是冒傻气。托洛茨基万岁!”,本句译文出自上海译文出版社。

The novel, his first, sold well. But when later that year Soviet tanks rolled in, forcing his country back into line, “The Joke” disappeared from bookshops. He himself was kicked out of the Communist Party (he had been expelled before, in 1950, for being critical, but had reapplied) and was fired from his lecturer’s job at the Academy of Fine Arts. Since no one was now allowed to employ him, he played dance gigs in the taverns of mining towns. Eventually, though, there was nothing doing in Czechoslovakia, so he and his wife Vera left for France, and stayed.

这本书是他的小说创作处女作,销量可观。但随后,当苏联的坦克驶进捷克,他的国家被迫回归阵营,而《玩笑》也从书店消失了。他本人则被开除捷共党籍(1950年他就因批评言论被开除过,后来又重新申请加入),失去了在电影学院的讲师工作。因为那时没人敢聘用他,他只得靠在矿场小镇的酒馆里弹奏些舞曲混口饭吃。由于在捷克斯洛伐克实在无事可做,最终他和妻子薇拉去了法国,并定居在那。

In retrospect, writing “The Joke” had been a bad decision. But it was good at the time. That was life. You had only one, with no second or third chances to take a different course. His novels were full of characters struggling, like him, to unpick the past, predict the future and, on the basis of that, jump the right way. In the most famous of them, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, the protagonist Tomas first appeared standing at a window, ruminating. Should he invite the lovely bartender Tereza to his room, or not? Would he get too involved? If so, how would he get out of it? After spending the night with her, the questions only multiplied.

事后想想,写《玩笑》是个错误。但在当时却是个好主意。这就是人生。你只有一次机会,没有第二次、第三次机会去选择不同的道路。他小说里都是像他一样在苦苦挣扎的人物,想要拆解过去、预测未来,并据此踏上人生坦途。在他最著名的小说《生命中不能承受之轻》中,主角托马斯一出场便是在窗前踌躇:到底要不要邀请可爱的餐馆服务员特瑞莎来自己的房间呢?他会不会陷得太深了?如果会,他该怎么摆脱?和特瑞莎共度一夜之后,托马斯更纠结了。

Tomas, like his creator, made a bad (or good) decision to defy the party. He lost his post as a surgeon and became a window cleaner. He also decided, for good or bad, to stay with Tereza. But all through the novel he had wrestled with his creator’s favourite theme, the weighing of opposites. The Greek philosopher Parmenides had stated, in particular, that lightness was positive and heaviness negative. Lightness was the realm of the soul, space, separateness and freedom; heaviness was to be earth-and-body-bound, rule-bound and constricted. Clear enough.

小说中的托马斯和昆德拉一样做了个错误的(亦或是正确的)决定,那就是与党作对。他丢了外科医生的工作,成了一个擦玻璃的清洁工。同时他不管不顾地决定要和特瑞莎在一起。但是通篇小说里托马斯都无法摆脱作者最喜爱的主题——两极间的权衡。希腊哲学家巴门尼德曾提出,轻为正,重为负。轻是魂、是空、是离、是自由;重是地、是身、是法、是限制。一目了然。

But not so fast. Lightness also made both history and life insubstantial, airy as a feather, the happenings of a day. It justified betrayal, irresponsibility andbreaking ranks(as he from the party), where heaviness stressed duty and obedience. Most important, lightness was about forgetting, and heaviness insisted on remembrance. What was the self, but the sum of memories? In “The Book of Laughter and Forgetting” the heroine, Tamina, clung constantly to the memory of her dead husband even when making love with other men. Was that a good or a bad thing?

但暂且先勿急下如此论断。轻亦令历史和生活变得虚幻,飘浮如鸿毛,平凡若朝暮。轻是背叛、失责和决裂(正如他脱离共党)的堂皇借口,而重则强调责任和服从。最重要的是,轻所以遗忘,而重所以铭记。自我不就是记忆的总和吗?在《笑忘录》中,女主角塔米娜对亡夫一刻都不曾忘记,甚至在跟其他男人做爱时也如此。这又是好是坏?

The question applied especially to Czechoslovakia, in its highly vulnerable position on the map. How could it survive without remembering its past great men, Hus, Comenius, Janacek, Kafka, or without the language they had spoken? Memory gave it identity, and gave Czechs themselves the only power they had against the states that oppressed them.In 1967 Mr Kundera appealed to fellow-writers to seize the moment with their pens. But he still resisted the thought of enclosing cultures within borders. Borders between ideas were there to be crossed.

鉴于捷克斯洛伐克极其敏感的地理位置,这一问题显得尤为贴切。如果捷克斯洛伐克忘记自己历史上的伟人——胡斯、夸美纽斯、亚纳切克、卡夫卡,或者忘记自己的语言,那它将如何延续?记忆承载着它的国家身份,也赋予捷克人民反抗他国压迫的唯一力量。1967年,昆德拉呼吁同行把握时机拿起笔杆。但他仍然抵制文化以国别论的观点。观念之间的边界是要跨越的。

注释:

1.胡斯:c.1369-1415,捷克神学家、哲学家和宗教改革家。

2.夸美纽斯:1592-1670,捷克著名教育理论家和实践家。

3.亚纳切克:1854-1928,捷克作曲家,代表作品《卡佳·卡巴诺娃》。

In Paris after 1975, living in an attic flat on the rue Récamier, feasting on frogs’ legs and eventually writing a trio of novels in French, it seemed to him that notions of “home” and “roots” might be as illusory as the rest of life. His Czech citizenship had been revoked and, though he still mostly spoke Czech, he was almost indifferent when, in 2019, he got it back. Like Goethe, he saw literature becoming global and himself as a citizen of the world.

1975年以后昆德拉住在巴黎雷卡米尔街的一套阁楼公寓里,享用蛙腿大餐,最终用法语写了三部曲小说。对他而言,“家”和“根”的概念可能跟余生一样虚妄。他的捷克国籍曾被撤销,尽管他大部分时间仍讲捷克语,但在2019年重获捷克公民身份时,他几乎无动于衷。像歌德一样,他认为文学正日益全球化,而他自己则是世界公民。

He had been one for a long time. His youthful reading was mostly French: Baudelaire and Rimbaud, but especially Rabelais and Diderot. French wit and experiment wonderfully foiled the socialist realism imposed on art and literature by the post-war Soviet regime. He fed it into his writing to defy the kitsch all around him. Sadly, it was kitsch he had fallen for himself when, at 18, he eagerly joined the party: all those heavy, emotional images of wheatsheaves, mothers and babes, hero-workers brandishing spanners, the glowing brotherhood of man. He saw himself as a knife-blade, cutting through the sweetish rose-tinted lies to show the shit—and the mystery—beneath.

一直以来,他都是一位世界公民。他年轻时阅读的大多是法国文学:波德莱尔和兰波,但尤其爱读拉伯雷和狄德罗。法式智慧和探索绝妙地抵挡了战后苏维埃政权强加给艺术和文学的社会主义现实主义。昆德拉将法式(文化艺术)影响融入自己的写作,以挑衅着充斥他周围的媚俗文化。悲哀的是,他本人也未能免俗。他在18岁时积极入党:一捆捆麦束、母亲和婴孩、挥舞扳手的英雄工人,闪闪发光的兄弟情谊,为这些沉重而感染力十足的宣传画面所诱惑。他视自己为刀刃,划破甜美的玫瑰色谎言,让底下的污秽和神秘一览无余。

注释:

1.波德莱尔:1821-1867,法国十九世纪最著名的现代派诗人,代表作《恶之花》。

2.兰波:1854-1891,法国象征派天才诗人,代表作《元音》。

3.拉伯雷:1494-1553,文艺复兴时期法国人文主义作家之一,代表作《巨人传》。

4.狄德罗:1713-1784,法国启蒙思想家、哲学家、戏剧家、作家。

Because truth was mysterious. And novels were a wide-open territory of play and hypotheses where he could question the world as a whole: digressively like Sterne in “Tristram Shandy”, or adventurously, like Cervantes’s Don Quixote. No answers, questions only; answers (in advance) were what kitsch provided. He played with philosophical musings, psychological analysis, investigations of misunderstood words, irony, eroticism and dreams.It could make a mish-mash for readers, especially Anglophone ones, and no other novel did as well as “Unbearable Lightness”, though “Laughter and Forgetting” and “Immortality” sold respectably.The Nobel talk came to nothing, and he was glad, because he preferred reclusive delving to any sort of fame.

因为真理就是捉摸不透的。对于昆德拉来说,小说的世界宽广无垠,可以大胆发挥,任意想象,还可以质疑整个世界:既可以像斯特恩写《项狄传》(Tristram Shandy)那样离散,也可以如塞万提斯写《唐·吉诃德》(Don Quixote)那般大胆。他抛出问题,却没有给出答案;只有媚俗的作品才会预设答案。昆德拉在作品中进行哲学沉思和心理分析,探究被误理解的语句、反讽、性爱和梦境。他的这种风格对读者来说,尤其是英语读者,可能会无所适从,但《生命中不能承受之轻》仍然大卖,超过了同样畅销的《笑忘录》和《不朽》。诺奖终究没来;不过他挺高兴,因为比起追名逐利,他更喜欢离群索居式的钻研探索。

He liked to call his novels “polyphonic”: a word learned from his father, a concert pianist and musicologist. The many voices, parts and motifs in his work were united by “novelistic counterpoint” into a single music. His chief hero in the enterprise was Janacek, whose photo hung beside his father’s in the Paris flat: a composer who had refused to write by the rules but made directly for the heart of things. He doubted he himself had got anywhere close. Since the world couldn’t be stopped in its headlong rush, it was best just to laugh at it. The devil laughed, because he knew life had no meaning; the angels, as they flew over, laughed too, knowing what the meaning was.

昆德拉喜欢用“复调”一词来形容自己的小说,这个词是从他父亲那里学到的。他父亲是一位音乐会钢琴家兼音乐学家。在他的作品中,不同的声音、片段和主题通过“小说式的对位法”融合成一曲乐章。在这方面,昆德拉最崇拜的是亚纳切克,在他巴黎的家中,亚纳切克的照片就挂在他父亲照片的旁边。亚纳切克不遵循传统的作曲法则,其创作直指事物的本质,而昆德拉并不确定自己是否达到了这种境界。既然世界匆匆向前,不可抵挡,笑对便是最好的选择。恶魔发出欢笑,因为他知道生命毫无意义;而飞跃苍穹的天使也在欢笑,因为他们知道生命的意义是什么。

注释:

莱奥什·亚纳切克(Leoš Janáček,1854年—1928年)是一名捷克作曲家,1854年7月3日生于摩拉维亚东部的胡克瓦尔迪。代表作品《卡佳·卡巴诺娃》。1928年8月12日卒于俄斯特拉发。

As a child he often sat at the piano playing two chords fortissimo, C minor to F minor, until his father furiously removed him. But as those chords became heavier he felt himself grow lighter until, in a moment of ecstasy, he seemed to float free of time. If that was unbearable lightness, he—and many others—spent an awful lot of their brief, insignificant lives trying to find it again.

昆德拉小时候经常坐在钢琴前,重重地来回弹奏C小调和F小调和弦,直到父亲气冲冲地把他拉走。不过,和弦弹得越重,昆德拉就感觉自己变得越轻盈,直至陷入一阵狂喜,仿佛摆脱了时间的桎梏,开始随音乐飘浮。如果说那种感觉就是“不能承受之轻”,那么可以说,昆德拉和其他许多人都曾穷极短暂而微不足道的一生,试图再度找寻这种感觉。

翻译组:

Lee,爱骑行的妇女之友+Timberland粉

Alfredo,清纯男高体验卡仅剩几个月到期

Qianna,对语言有点敏感,对逻辑十分执拗,对摇滚太过着迷

校对组:

Constance,痛终有时,爱必将至

UU,允许别人做别人,允许自己做自己

Rachel,学理工科,爱跳芭蕾,热爱文艺的非典型翻译(年年备战一口)

限 时 特 惠: 本站每日持续更新海量各大内部创业教程,一年会员只需98元,全站资源免费下载 点击查看详情

站 长 微 信: lzxmw777